Now is the time to incentivize e-bike ownership

- Author: Tyler Madell

- Date: November 8, 2024

Part 1: Why e-bikes? What if I told you that there was a low-cost transportation policy measure that New York…

Content in this document is disseminated by NCMM in the interest of information exchange. Neither the NCMM nor the U.S. DOT, FTA assumes liability for its contents or use. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and not of the National Center for Mobility Management.

The dual shock of a global pandemic and what looks like to be a severe and prolonged economic crisis, has changed our personal mobility patterns.

In an effort to curb exposure to the virus, people have shifted to more individualized modes of transportation, including lightweight vehicles such as bicycles or scooters, especially electric ones. These are collectively known as “micromobility.”

The interest in cycling has reached unprecedented levels, making it very hard to purchase a bicycle, obtain spare parts, or get a bike repaired; across North America, bike shops have sold out of their inventory. In major metropolitan cities such as New York and Paris, bills have been passed to expand cycling infrastructure as a means to promote and maintain the accessibility and safety of cycling.

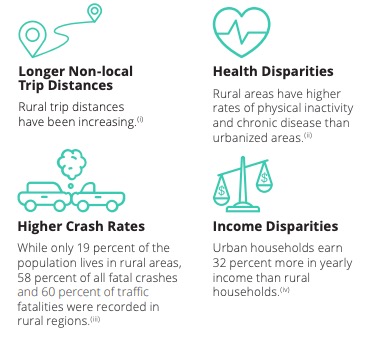

There are some key differences between rural and urban communities that impact the uptake of micromobility. Trip distances are generally longer in rural areas and traditional public transit is not as widely available as in urban areas, so people default to personal cars as the mode of choice.

As statistics show, more driving translates into a higher risk of being involved in a fatal crash: a 2016 report commissioned by the Federal Highway Administration found that 58% of all fatal crashes occur in a rural context. The same report also highlights that the more sedentary lifestyle that comes with driving as opposed to more active means of transportation directly translates into health problems such as diabetes and heart diseases.

While it may seem like a lost cause to introduce micromobility in rural context, it is far from it.

This article will outline two steps to increase success of micromobilty in rural America and why now is the time to introduce it.

Cycling has been part of rural communities in the United States for over a century. But many small and rural communities are located on State and county roadways that were built to design standards that favor high-speed motorized traffic, resulting in a system that makes walking and cycling less safe and uncomfortable.

With a general lack of dedicated, protected infrastructure for active transportation and micromobility users, users tend to ride, park and store micromobility devices on sidewalks – often creating safety hazards and accessibility issues for pedestrians.

To increase the appeal and usage of micromobility vehicles in rural America again, communities have to focus on building out safe infrastructure to support micromobility. In particular it’s important to think about a complete network where one major cycle superhighway connects different workplaces and rural centers across municipal borders, with each municipality having individual cycle routes within that allow people to safely and comfortably get to their end destination.

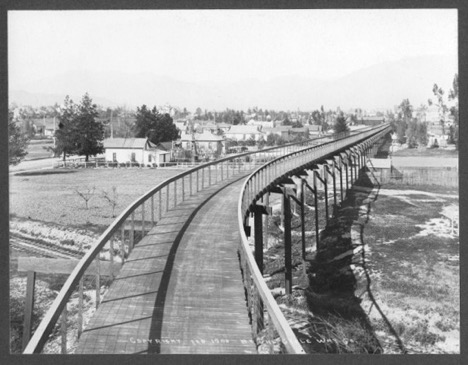

In fact, this cycle superhighway is not a new idea. In the late nineteenth century, the introduction of the modern bicycle sparked a nation-wide bicycle craze in the United States. Fervor for the two-wheeled vehicle especially resonated in Southern California, a region that prided itself on ideal year-round conditions for healthy outdoor activity. Yet settlements were scattered and connected mostly through dirt roads. So Pasadena’s Mayor Horace Dobbins pushed for an ambitious bicycle freeway connecting the Crown City to Los Angeles through an elevated bike path.

Perhaps now is the time to reinvest in micromobility infrastructure. Because there is a high return on investment from installing cycling networks. The increase in cyclists and other micromobility users diverts cars from streets, resulting in reduced traffic and pollution, while increasing pedestrian and cyclist safety and property values.

While new forms of mobility, especially e-scooters and dockless bikes, initially went mostly unregulated and operated in the “grey zone” of policy, in the last two years city planners have increased regulation significantly.

For example, in 2018, Portland, OR set an overall cap of 2,500 e-scooters in the city and imposed stringent curb usage rules. It also implemented a street use fee of 25 cents per scooter trip and required at least 20 percent of scooters to be deployed to lower-income East Portland. In 2019, Portland set a goal to reduce the overall number of scooter operators to 1-3 companies for a period of 2-3 years, in order to better ensure the financial viability of those companies.

While this stringent regulatory approach can work in larger cities, because micromobility providers line up to serve these markets, they are not beneficial for smaller rural communities that struggle to attract players. The City of Charlottesville in Virginia, for instance, received only one application to provide dockless scooters and bikes from lesser known operator VeoRide.

For smaller communities, the way forward is partnerships with potential providers. A good example of this is the collaboration between the City of Vicksburg, Mississippi and Blue Duck, a San Antonio based micromobility provider.

With a population of just over 23,000 citizens, Vicksburg is not your typical micromobility market, yet in September this year, Blue Duck started rolling out an electric scooter service. “Despite its smaller size, Vicksburg has a compact, dynamic downtown business district that attracts residents and visitors alike,” says Andre Campagne, CEO of Blue Duck. Community leaders recognized the value of getting residents and tourists around town using micromobility.

Blue Duck strategically focuses on communities that have a population of less than 1 million and a local college or university. Champagne mentions that smaller cities are often more open to forming an exclusive partnership, which fosters a more collaborative relationship. In fact, in the case of Vicksburg, Blue Duck was supported by everyone at City Hall, including local lobbying efforts to change state legislation so micromobility services could even be offered in Mississippi.

Rural communities have an opportunity to use policy to drive change, yet as the Vicksburg example shows, a more collaborative approach with a view on long-term sustainability and viability.

Increasing micromobility has several benefits for communities, especially in a rural context.

Micromobility services have shown incredible resilience during this pandemic because they allow for travel with physical distancing. Investors have recognized this as well and opened the funding faucet again, and that includes those that serve smaller communities.

Even the incoming Biden Administration recognizes the value of micromobility and is promising to help cities invest in infrastructure that supports it. Smaller communities should ensure they receive a portion of that funding. If they do and with the right partner, micromobility can succeed in rural communities of the United States.

———

Sandra is a Shared Mobility Architect with movmi. To date, she has been involved in more than 60 shared mobility projects world-wide. Her work spans across Mobility-as-a-Service programs in Vancouver, microtransit for rural island communities, e-mopeds in Brooklyn as well as the numerous carshare services, including ekar the first service in the Middle East. Connect with her on LinkedIn.

Part 1: Why e-bikes? What if I told you that there was a low-cost transportation policy measure that New York…

As technology advances and a focus on environmental sustainability grows, e-bikes have emerged as a convenient and eco-friendly mobility solution.…

It’s been a busy month in the world of mobility and technology: several big transit agencies announcing big plans on…

Amsterdam boasts that it’s the bike capital of the world. Smaller North American cities can learn from their best practices.…

It’s been a busy first quarter of 2023, and a lot’s been happening in the world of transit technology news.…

Have more mobility news that we should be reading and sharing? Let us know! Reach out to Sage Kashner (kashner@ctaa.org).

There was a problem reporting this post.

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

Please note: This action will also remove this member from your connections and send a report to the site admin. Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.